eurobanks/Getty Images

Trump’s push for executive order loyalty risks undermining the federal workforce and the Constitution

COMMENTARY | Federal workers are being asked to prove their loyalty to Trump’s agenda, but history shows that when politics overtakes merit, government performance suffers.

Donald Trump launched his presidency with a blizzard of executive orders unlike anything in recent memory—more than three times as many as in Joe Biden’s first 100 days, seven times as many as Barack Obama, and 13 times as many as George W. Bush. And he expects federal workers to be accountable to him.

To underline the point, his Office of Personnel Management has put out a new hiring plan for federal workers and a training plan for the Senior Executive Service. Applicants for a job must demonstrate how they would “help advance the President’s Executive Orders and policy priorities.” The training plan for new SESers begins with sessions on “President Trump’s Executive Orders.”

The administration is convinced that “many career federal employees use their positions to advance their personal political or policy preferences instead of implementing the elected President's agenda,” as the proposed rule creating the new Schedule Policy/Career (formerly known as Schedule F) puts it. To the degree that happens—rarely, but certainly occasionally—it is wrong and unethical.

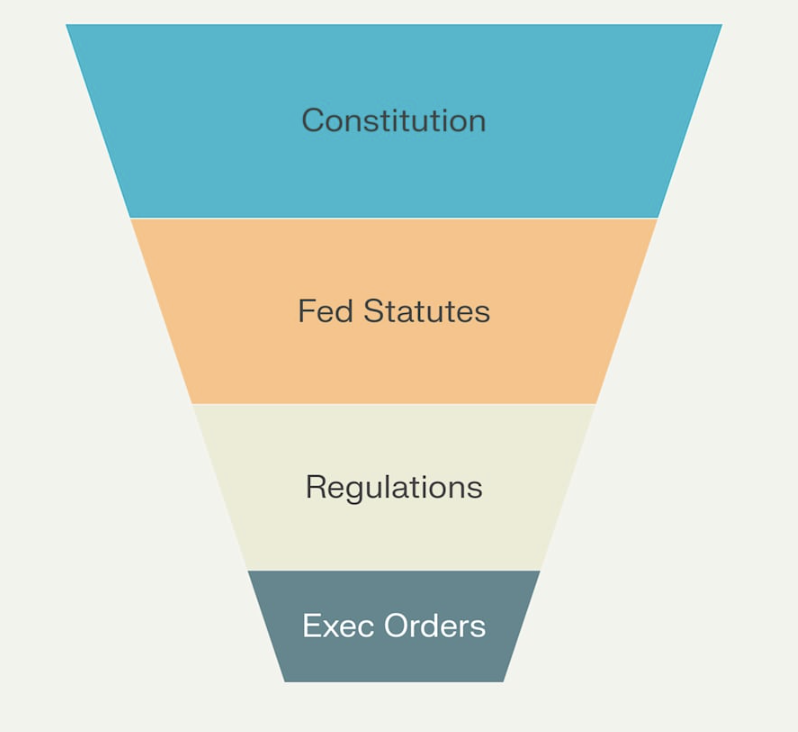

At the same time, however, feds need to be accountable to more than the president’s executive orders. EOs, in fact, are at the bottom of the federal legal chain, not the top.

The Constitution is the basic law of the land. Congress passes laws to define policy and the delegation of power to execute them becomes framed in regulations, through the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946. Presidents can—and do—emphasize their own priorities through executive orders, and they always decide how much emphasis to put on which programs and regulations. If they don’t like earlier EOs, they can issue their own orders to wipe them out, and they can instruct agencies to change regulations that aren’t in sync with the administration’s priorities.

But the bottom line is that federal officials are accountable to the EOs, but also to much more, including the professional standards of their professions. Anyone who has listened to more than a few seconds of the air traffic control radio knows how much we need the controllers and how it’s not a job for amateurs.

So when Team Trump complains that federal employees don’t always follow presidential directives, it’s often because the employees are in the crosscurrents of the balance of powers. That’s a feature, not a bug of the constitutional system that the founders created. It’s a bug, not a feature, that annoys team Trump.

We can’t squash that bug without undermining our constitutional system.

And we need to remember, as well, that the public values the quality of government much more than who it’s loyal to. A poll conducted this time last year found that 95 percent of those surveyed agreed with the statement, “civil servants should be hired and promoted based on their merit, rather than their political beliefs.”

Before the creation of the politically nonpartisan merit system with the Pendleton Act of 1883, the government just wasn’t very good at doing what the people wanted done. Postal workers found an easy way to deal with the daily flow of mail—they just locked it up in a back closet. British and Prussian customshouses were four to five more times more efficient than those in the U.S. The Europeans relied on professionals; in America, these were plum political jobs.

The more the administration focuses on hiring and training employees who support executive orders, the more the president risks programmatic and, therefore, political suicide. That certainly doesn’t mean that Team Trump ought to turn the government over to the “deep state” or that feds get a free shot at kneecapping the president’s agenda.

But focusing on short-term responsiveness to executive orders would serve the president badly and the country’s long-term interests even worse. We shouldn’t have to painfully learn the lessons of the Pendleton Act all over again.

NEXT STORY: NASA renews its push to slash its workforce