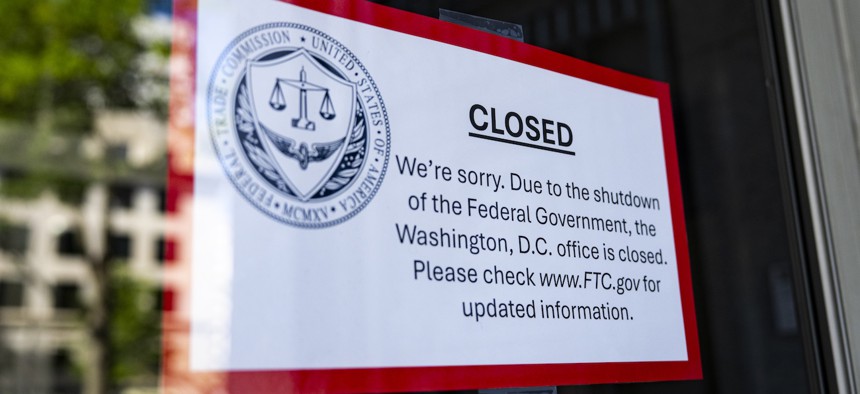

The federal government has been shut down since Oct. 1. Al Drago/Getty Image

Carpools, side jobs and food banks: How feds working through the shutdown are navigating delayed pay

Employees working without pay are worried about piling bills and distractions in jobs with no room for error.

In two weeks, one civilian U.S. Coast Guard employee is facing the cancellation of both her car and homeowner’s insurance.

She is working during the shutdown, but unlike her uniformed colleagues, she will not be paid on time. This week, like a majority of the federal workforce, she received a partial paycheck. Her next paycheck will be delayed as long as the shutdown drags on. If it does not hit her account at the normal time, she has no plan to make those insurance payments.

“If I were [furloughed] I would know what to do, I would go get another job,” said the employee, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution. “But I have to work.”

The employee is “excepted” during the shutdown, meaning her job has been deemed necessary to protect life or property. She continues to work each day, like around 70% of federal employees, most of whom are doing so only on the promise of retroactive pay once the government reopens.

The Coast Guard worker is a single parent with three dependents at home. She would like to work in a temporary job with Uber or Amazon, but her full-time employment and familial responsibilities prevent her from doing so. Instead, she has started going to a food bank to save whatever money she can. Her child care is allowing delayed payment, for now.

“My creditors haven’t been so kind,” she said.

Nearly 700,000 federal employees are currently home on furlough, all of whom received only partial paychecks in recent days since the last few days of the pay period occurred after the shutdown began. Another roughly 1.5 million are working, a portion of whom are getting normal paychecks as their agencies are using leftover or otherwise available funds. The majority, however, are working without on-time pay.

“We don’t know when our next paycheck is going to come,” said Pete LeFevre, an air traffic controller at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, D.C. “We don’t know how long the shutdown is going to last. As we get closer to getting a zero paycheck, bills will continue to come in. The bills are piling up on the kitchen counter.”

In 2019, a rise in absenteeism from controllers and Transportation Security Administration staff toward the end of the record-setting 35-day shutdown helped spur Congress to enact funding and reopen government. LeFevre said he and his colleagues remain committed to showing up to work, but warned that his colleagues are already holding discussions about how they are going to deal with the financial uncertainty.

LeFevre said some of his colleagues work six days per week at their Federal Aviation Administration jobs, but are starting to spend their day off driving for Uber to pick up extra cash.

“You gotta do what you gotta do,” he said. “We have families, we have responsibilities. We have to make it work.”

Nick Daniels, president of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, said the National Airspace System cannot afford to have distracted or overtired employees monitoring it.

“You don’t get to have a moment when you’re not perfect,” Daniels said. “And by the way, on top of it, let’s [conduct] the social experiment of seeing how long you can do it without money.”

A corrections officer in the Justice Department’s Bureau of Prisons said the recent check only providing pay through Sept. 30 already has some of his colleagues “scrambling to make ends meet,” particularly as they have no sense of when the next paycheck might arrive.

“Some have started to look at other jobs and others are looking at a part-time job,” the officer said. “If this drags on, we will see staff start to exit for more stable work.”

The drain would exacerbate the exodus of employees who have already departed for the recruitment incentives and elevated pay being offered by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the employee said. Agency officials have for a decade warned of staffing shortfalls, a problem worsened earlier this year when the agency was briefly subject to a hiring freeze and a funding shortfall forced pay cuts for 23,000 employees.

“We can’t sustain this for much longer without long-term damage,” the corrections officer said.

An excepted Agriculture Department employee working during the shutdown said the frustration is both personal and professional. She is part of a bare bones staff still working at her agency, and the furloughs are threatening longstanding research projects.

“All of our field work is sitting out there, not getting done,” she said. “Months of work and data potentially trashed because we’re not allowed to do our jobs.”

Colleagues are checking in on each other to ensure their shelves at home are still stocked, the employee said.

“We’re all helping each other out and doing the best we can,” she said. “Do people need anything personally and are not going to be able to cover it due to missed paychecks?”

LeFevre, the air traffic controller, similarly said coworkers are looking for ways to support each other. In the break room, he said, they are sharing as much information as possible, ranging from which institutions are offering no-interest loans to shutdown-impacted personnel to helping save on gas money by carpooling to work.

“My colleagues and I are going to do everything we can for as long as we can,” LeFevre said. “We rally around each other. We’re a family. We’re going to help each other out.”

While LeFevre alluded to employees lasting as long as they can, Daniels, the union president, said there should be no expectation that air traffic controllers try to leverage their vitality to the flying public to pressure lawmakers. NATCA’s website has added a warning that it does not “endorse, support or condone” taking any collective action that undermines the airspace system.

“Air traffic controllers do not start shutdowns and we’re not responsible for ending them,” Daniels said.

The Coast Guard civilian said an added frustration came from the limited work she can currently carry out. As a contracting official, she said, day-to-day operations have slowed as no new money can go out the door. Still, the employee was warned by her supervisors not to take any leave—which would lead to her temporarily being placed on furlough status—as doing so would be noted by higher ups.

“It’s boring, boring, boring,” she said of her shutdown work days. “There isn’t a lot to do.”

Share your news tips with us: Eric Katz: ekatz@govexec.com, Signal: erickatz.28

NEXT STORY: With funding for courts in question, Congress stuck in shutdown gridlock for day 16